Calisthenics statics are some of the most impressive and demanding bodyweight training exercises. Elements such as the Full Planche, Front Lever, Maltese, or Human Flag require not only enormous strength but also high body awareness, mobility, and biomechanical understanding.

In this article, you will learn about every static hold that exists in calisthenics through a complete and organized diagram. This will allow you to easily identify the technical differences between each static and the muscles worked by each. Additionally, at the end of the article, I will recommend the best statics for beginners who are taking their first steps in calisthenics.

What is a Static in Calisthenics?

A static is an exercise that consists of maintaining a body position for a short interval of time. Therefore, statics are isometric exercises; this means that the muscle length remains constant: it neither shortens nor stretches. Consequently, they do not involve any type of joint movement.

Types of Muscle Contraction

However, the concept of a static, specifically in calisthenics, is slightly more complex: every static is an isometric, but not every isometric could qualify as a static.

What is NOT a Static?

On one hand, statics refer to those body positions that require a great deal of strength and, consequently, can only be held for a very short interval, approximately 2 to 10 seconds. For example, the abdominal plank is an exercise that a large percentage of the world's population can hold for more than 10-60 seconds, and some people can even hold it for hours; thus, it is not considered a static.

On the other hand, statics are very specific positions that are accepted as such, generally within the world of freestyle and powerfree. For example, holding the final position of a one-arm pull-up, regardless of how much strength it requires, is not accepted as a static.

Classification of Statics

To understand all calisthenics statics in an easy and simple way, I decided to classify them into a complete diagram. In this way, it will not only be easier to learn them, but you will also be able to recognize their technical differences and the muscles worked by each one.

To begin, we can divide all statics into two major categories: hip-dominant statics and shoulder-dominant statics, the latter representing approximately 95% of all statics.

Hip Joint

The first category includes hip-dominant statics. This means that the force is produced mainly in muscles that cross the hip joint, specifically the hip flexors (Iliopsoas, rectus femoris, sartorius, etc.).

The first is one of the most popular and easiest statics in calisthenics: the L-Sit. This exercise requires a minimum of strength in the hip flexors and the abdomen.

L-Sit

The next static is the V-Sit, which is more advanced, as it requires very good hip mobility: strength in the end range of hip flexion and flexibility in the hip extensor muscles.

V-sit

And the final static in this category is the Manna, which, in addition to the above, also requires great shoulder mobility. This static is performed mainly in artistic gymnastics; very few calisthenics athletes actually perform this element.

Manna

Shoulder Joint

In the second category are all the shoulder-dominant statics, meaning the force is produced mainly in muscles that cross this joint.

The statics in this category can be divided according to the plane of movement in which the exercise is executed: the sagittal plane and the frontal plane.

Sagittal Plane

Most statics are found in the sagittal plane, so this classification will have several levels.

To start, the statics will be divided according to the muscular action performed in this plane: shoulder flexion and shoulder extension.

Next, they will be divided according to the number of limbs involved: bilateral and unilateral.

Within bilateral statics, these can be divided according to their point of support: on the hand or wrist, or with support on the forearm or arm.

Finally, if the support point is on the hand or wrist, these can be divided according to the elbow angle: straight arm and bent arm.

Shoulder Flexion

We will begin with the statics in the shoulder flexion category. Therefore, all the following statics will work the muscles responsible for this action: the anterior deltoid and the pectoralis major, specifically the clavicular head.

It is important to keep two things in mind: first, there will be slight changes in muscle activation due to modifications in joint positions; and second, the core muscles, forearm muscles, and, to a lesser extent, some lower body muscles will always be working.

Straight Arm

After all this classification, let us now review the statics in this category. In this case, we can organize the statics according to the position of the arms.

The first static we will see is the Full Planche, one of the flagship statics of calisthenics. In this static, and in most of those we will see later, the body must remain in a completely straight line parallel to the ground, with the arms at approximately 45° of shoulder flexion.

Full planche

If we bring this angle to 0°, we get a new static known as the Dead Planche. As we can see in the reference images, unlike the Full Planche, the arms are at the same height as the body.

Dead planche

And if we bring the arms behind the body, we get the famous Back Lever, another very popular exercise in the world of calisthenics.

Back Lever

Returning to the Full Planche, if we open the arms, we get the Wide Planche, and if we open them to the maximum, we reach a static known as the Maltese, although some also call it the Airplane.

Maltese/Airplane

It is important to keep in mind that these statics are not exact points, but ranges that are not completely defined. So, it is normal for debates to arise about at what point a Wide Planche becomes a Maltese.

Maltese

However, we can also reach the Maltese from the Back Lever: first, we have the Wide Back Lever and then the Back Lever SAT (Straight Arm Touch), which means that the body must touch the bar at all times while maintaining straight arms.

Back Lever SAT

Bent Arm

This category includes statics that are performed with bent or flexed arms.

The first is the Pseudoplanche, also known as the Bent Arm Planche or 90° Hold. But beware, it should not be confused with a pose known as the Elbow Lever, since in the latter, the arms are supported on the abdomen, so it does not really require much strength. In contrast, in the Bent Arm Planche, the arms are placed at the sides of the body, which does require a high level of strength.

Pseudoplanche

And the second static in this category is the Back Lever Touch, where once again the body must touch the bar, but in this case with flexed elbows.

Back Lever Touch

Forearm/Arm

In this category are the statics in which the forearm or the entire arm is supported. These are much less known and practiced.

The first is the Prayer Planche and the second is the Forearm Planche or Bicep Planche, which are two different variants of the plank on the forearms. The third is the Box Maltese Hold, where the entire arm is supported on the surface. This last one, although it can be considered a static, is usually used more as a progression or accessory exercise for the Full Planche and Maltese.

Prayer Planche

Forearm Planche

Maltese Box Hold

Unilateral

In this category are the unilateral statics, that is, those performed with only one arm: the One Arm Back Lever, the One Arm Planche, and the One Arm Forearm Planche.

One Arm Back Lever

One Arm Forearm Planche

One Arm Planche

Shoulder Extension

Now we will move on to the shoulder extension category of statics, which work the muscles opposite to flexion: the latissimus dorsi, teres major, posterior deltoid, and even the long head of the triceps.

Straight Arm

The first static is the Front Lever, another of the flagship statics of calisthenics. In the Front Lever, as in the Full Planche, the arms are at approximately 45° of shoulder flexion.

Front lever

If we bring this angle to 0°, we get an extremely rare static that can be called the Dead Front Lever, although some may also know it as the Shoulder Width SAT.

Dead Front Lever

And if we bring the arms behind the body, we get the Reverse Planche, considered one of the most difficult statics in all of calisthenics (if not the most difficult).

Reverse Planche

Returning to the Front Lever, by opening the arms we get the Wide Front Lever, and by opening them to the maximum we reach the Victorian on rings or the SAT on the bar.

In this case, the Victorian can only be reached through this path, as to this day, there is still no one capable of performing a Wide Reverse Planche.

Victorian and SAT

Bent Arm

In this second category, we find a single static: the Front Lever Touch. As I mentioned before, this consists of touching the bar with the body.

Front Lever Touch

(@yudu_xinghang)

Forearm/Arm

In this category, we find two statics: the Victorian on floor and the Victorian on parallel bars. Although both are called Victorian, there are slight differences in the execution of each.

In the Victorian on floor, only the forearms are supported, and the elbows must be flexed so that the body remains in an elevated position and does not touch the ground. Meanwhile, the Victorian on parallel bars can be performed in different ways depending on the width and length of the parallels: it can be executed with the elbows slightly flexed and only the forearms supported, or with the elbows fully extended and the arm also supported.

Victorian on floor

Victorian on parallels

Two points of support

Up to this point, the classification was completely the same as that of the shoulder flexion category. All the statics mentioned so far have relatively only one support, whether on the hand or distributed across the entire arm. However, here we can find three statics that, in their execution, have a second point of support.

The first of these is the Dragon Flag, a very popular static in calisthenics and, in general, in the fitness world. This static consists of keeping the body totally straight using the hands and the upper back as support points.

Dragon Flag

The second static is the Shoulder Flag, which is practically a Dragon Flag but performed on a vertical bar. In this case, the second support point is found on one of the two trapezius muscles.

Shoulder Flag

The third static in this category is the Dragon Press. Again, this is a variant of the Dragon Flag, but with the arms at body level and supported on the ground. This exercise can be confused with the Victorian on floor, but remember that here the upper back is supported on the ground.

Dragon Press

Unilateral

Finally, we have the last static in the shoulder extension category: the One Arm Front Lever.

One Arm Front Lever

Frontal Plane

Now we are going to review all the statics that are executed in the frontal plane. In this case, there are not as many statics as in the sagittal plane, so we can divide them only according to the muscular action in this plane: shoulder adduction and abduction.

Shoulder Adduction

We will start with the statics in the shoulder adduction category. The main muscles responsible for this action are the latissimus dorsi, teres major, and pectoralis major.

In this category, we find only one static: the Iron Cross, a very popular element in men's artistic gymnastics. This consists of maintaining the body vertically with the arms extended to the sides, forming a cross with the body. This static can be combined with the L-Sit and V-Sit, significantly increasing its difficulty.

Iron Cross

Abduction

Now we will review the statics in the shoulder abduction category; the muscles responsible for this action are: the deltoid, specifically the lateral head, and the supraspinatus.

In this category, we have two statics. The first is the Inverted Cross, which, as its name indicates, is an Iron Cross with the body inverted. The second is the Japanese Handstand, which is a variant of the handstand with the arms wide open.

Inverted Cross

Japanese Handstand

Mixed

And finally, we have a static that combines the two previous actions: the Human Flag. In this exercise, the lower arm pushes against the bar (shoulder abduction), while the upper arm pulls from it (shoulder adduction).

Human Flag

Variations

Before concluding, I want to make two clarifications. First, these are the statics in their full and conventional form. However, each has different variations when making slight technical changes: according to the surface (floor, parallels, high bar, rings), according to the type of grip (prone, supine, neutral, or mixed), and other variations such as on fists, wrists, fingers, or dragon-style.

Second, in the world of calisthenics and bodyweight training, you will always find a new and strange exercise or variation: one-arm variations, assisted one-arm variations, and even extremely rare exercises. For this article, I mentioned the main and best-known ones in the world of calisthenics.

Frequently Asked Questions about Statics

What is the difference between a static and a dynamic in calisthenics?

In calisthenics, statics are body positions that do not involve movement; some also know them as tension elements. Dynamics, on the other hand, are acrobatic movements, spins, and tricks performed on the high bar, such as a 360 Swing.

How long should I hold a static in calisthenics?

At a competitive level, the athlete must hold a static for 2 to 3 seconds with good form for it to be considered valid. If your goal is to train a specific static, this will depend on the programming and periodization of the training plan. However, this time generally ranges from 5 to 30 seconds of hold per set.

What statics should I do if I am just starting in calisthenics?

One of the best statics for beginners is the L-Sit, because it is one of the easiest and fastest to achieve in calisthenics. In addition to the L-Sit, the Dragon Flag and the Back Lever are usually recommended, as they are also relatively accessible statics for those entering this world. Furthermore, as we saw in the classification, the Dragon Flag and the Back Lever work opposite muscles, so they complement each other very well and allow for a more complete workout. Finally, these two statics function as previous progressions to the Front Lever and the Full Planche, making them excellent options if you want to train these advanced statics later.

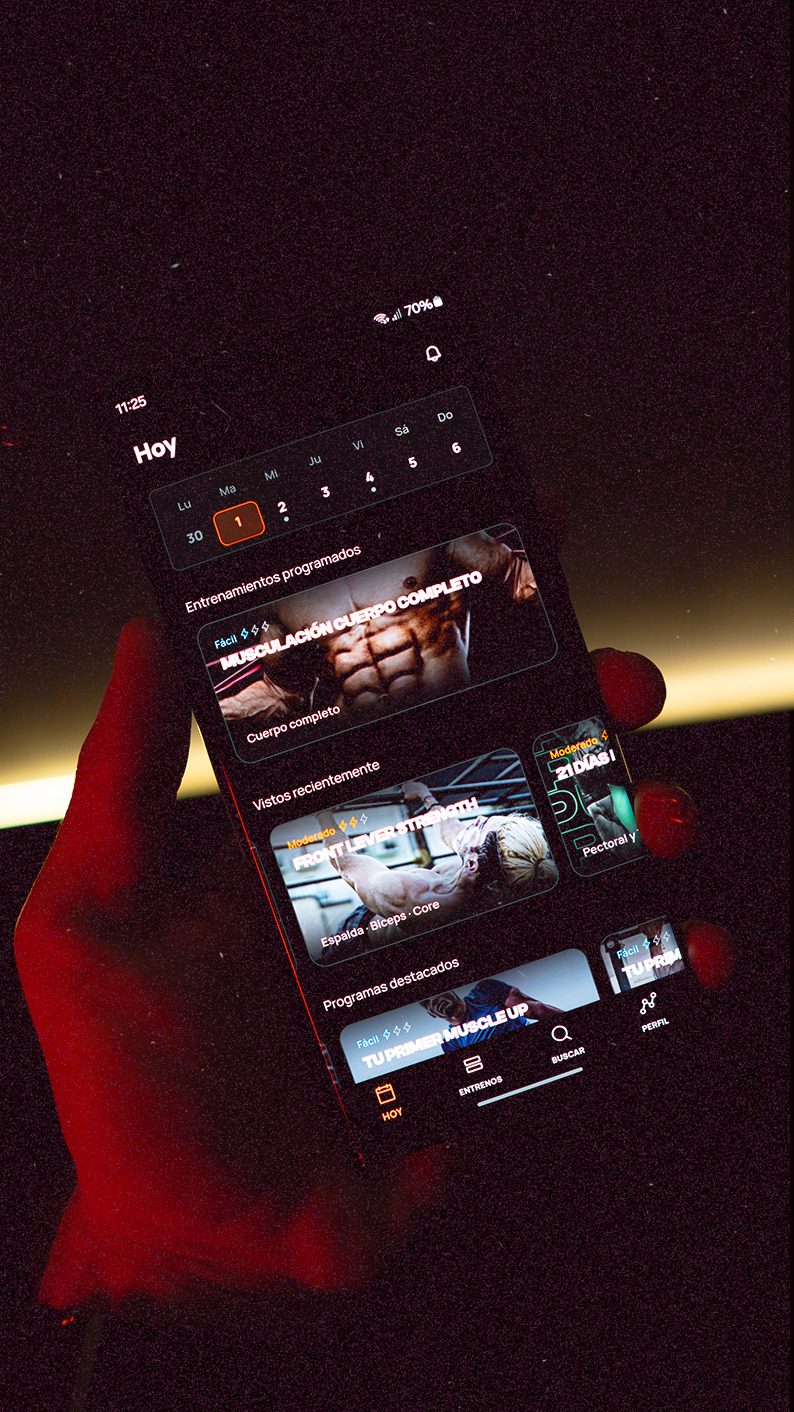

Remember that in our application Calisteniapp, you can find routines and programs to train these statics if you are interested. Additionally, I will be creating complete guides for some of the statics mentioned in this article, so stay tuned to the blog and my social media to know when new content is published.

Quiz personalizzato

Trova il tuo piano ideale

Rispondi a 7 domande rapide e ti consiglieremo il programma più adatto.

Unisciti alla nostra newsletter

NUOVI ARTICOLI OGNI SETTIMANA

Impara tutto quello che devi sapere sulla calisthenica

Calisteniapp

Inizia l'allenamento di calistenia e street workout