How to achieve your first pull up

Learn how to achieve your first pull-up from scratch with simple progressions, key exercises, common mistakes, and tips to progress faster.

One of the most important values in calisthenics is respecting strict technique when performing exercises, including full range of motion.

Over the more than 20 years of development that modern calisthenics has had as a sport, we have always taken pride in the cleanliness of our movements and the beauty of our execution compared to other sports or training methods.

Exercises like pull-ups, dips, push-ups, muscle-ups, planches, and more—if they weren’t done properly with clean technique, they weren’t considered worthy of a calisthenics athlete.

However, there are some exercises, or specific technical details of certain exercises, that have gone unnoticed and have been performed incorrectly for years—even by advanced athletes—without anyone calling it out. These mistakes happen even in competitions, with multiple judges carefully watching the competitor, yet they aren’t penalized.

That’s why today I want to highlight these exercises to raise awareness of this issue and ensure calisthenics stays true to its values and continues improving as a sport. Beyond simply pointing out the mistakes, we’ll also explore why this happens and how to fix it.

Whenever the technical specifications for this exercise are given, the rulebooks all state that the elbows must reach at least 90 degrees. It is always specified: the arms must bend until forming a 90-degree angle at the elbow joint.

And that makes sense because it’s a simple and objective way to measure whether the movement has enough range without being shortened to cheat. Another common standard is that the bar should touch the lower chest or xiphoid line, but this is much easier to manipulate. Depending on how much you bend at the hips, you can touch this line with very little range of motion or with the correct full range.

It’s similar to what happens with powerlifters in the bench press, where they arch their back so that the bar touches the chest with minimal movement. Or, for example, it reminds me of push-ups—if we said the standard was touching the ground with the nose, some people would just move their head forward to achieve that with minimal range.

That’s why I believe the 90-degree elbow angle should remain the reference, but it actually needs to be enforced. Currently, even in the most prestigious competitions that emphasize proper technique, this requirement is often ignored, and athletes perform straight bar dips with a very reduced range of motion.

It’s obvious why this happens: with a shortened range of motion, the reps are faster. And if athletes see that nothing happens, that they aren’t penalized for this incorrect execution, they naturally won’t sabotage themselves by doing them the slower, proper way. So, until judges enforce what’s written in the rulebook and require proper execution, this will continue.

To correct this, all it takes is a slight hip flexion, avoiding an upright position, which immediately allows for full range of motion. It’s a very simple adjustment, yet it transforms the exercise from having a limited range to a complete one. In fact, some rulebooks already specify that the hips must be flexed at 45 degrees, but even this isn’t always enforced.

Any experienced calisthenics athlete, any competition rulebook, and any judge will tell you that a proper pull-up requires full arm extension, reaching full lockout at the elbows.

Yet, once again, this is something that doesn’t happen in competitions, even in the strictest ones.

Endurance athletes have developed a way of performing pull-ups with a certain circular body motion—a technique or rhythm that allows them to perform reps at high speed while maximizing their effort for the best results. However, this circular rhythm prevents full elbow extension, as it would disrupt the flow of movement. But that’s not what the rulebook says, and judges shouldn’t allow it.

When we say “fully extend the arms” or “lock the elbows,” we don’t mean “almost fully extend the arms” or “almost lock the elbows but not quite.” It’s obvious that full elbow lockout means reaching the point where the arm is completely straight and the elbow joint can’t extend any further—that’s why it’s called “lockout.”

Again, this issue comes down to speed—endurance athletes aim to complete reps as quickly as possible to win. And once again, if judges allow it, they will continue doing reps this way.

To fix this, judges must be stricter, and athletes should find ways to perform pull-ups as fast as possible while still fully locking out their elbows. This presents some challenges since momentum and inertia change when doing them with the proper technique instead of the circular style mentioned earlier.

I won’t go into too much detail here because it’s essentially the same issue as with pull-ups. Both logically and according to every rulebook, dips and push-ups should require full elbow extension—not “almost fully extended” or “almost locked out,” but completely extended and locked.

Yet, once again, this standard is often ignored.

In dips, judges are also often too lenient with the 90-degree requirement, and it’s not fully enforced. Sometimes, they try to solve this by placing a fist under the athlete to ensure they lower enough to touch it. But from what I’ve seen, this doesn’t usually work—either the judge places their fist at a height where the athlete doesn’t actually reach 90 degrees, or, if they do place it correctly, they eventually adjust it upwards to match what the athlete is used to doing.

In other words, instead of enforcing the rulebook, judges end up being lenient and allowing the usual “almost 90 degrees.” I believe it would be simpler for the judge to visually assess the movement, warn the athlete if they aren’t going low enough, and if they don’t comply, simply not count their reps.

Finally, squats have a similar issue regarding knee flexion to at least 90 degrees.

All rulebooks generally state that you must reach or surpass this angle. However, when we talk about hitting 90 degrees, we have to visualize the central line of the athlete’s thigh—the position of the femur relative to the ground. And, once again, what typically happens is that athletes get close to 90 degrees but rarely meet the standard, and almost never surpass it.

The solution is the same as in the previous cases: as long as judges are lenient, athletes will find ways to be as fast and competitive as possible. So, once again, it’s up to the judges to enforce the rules.

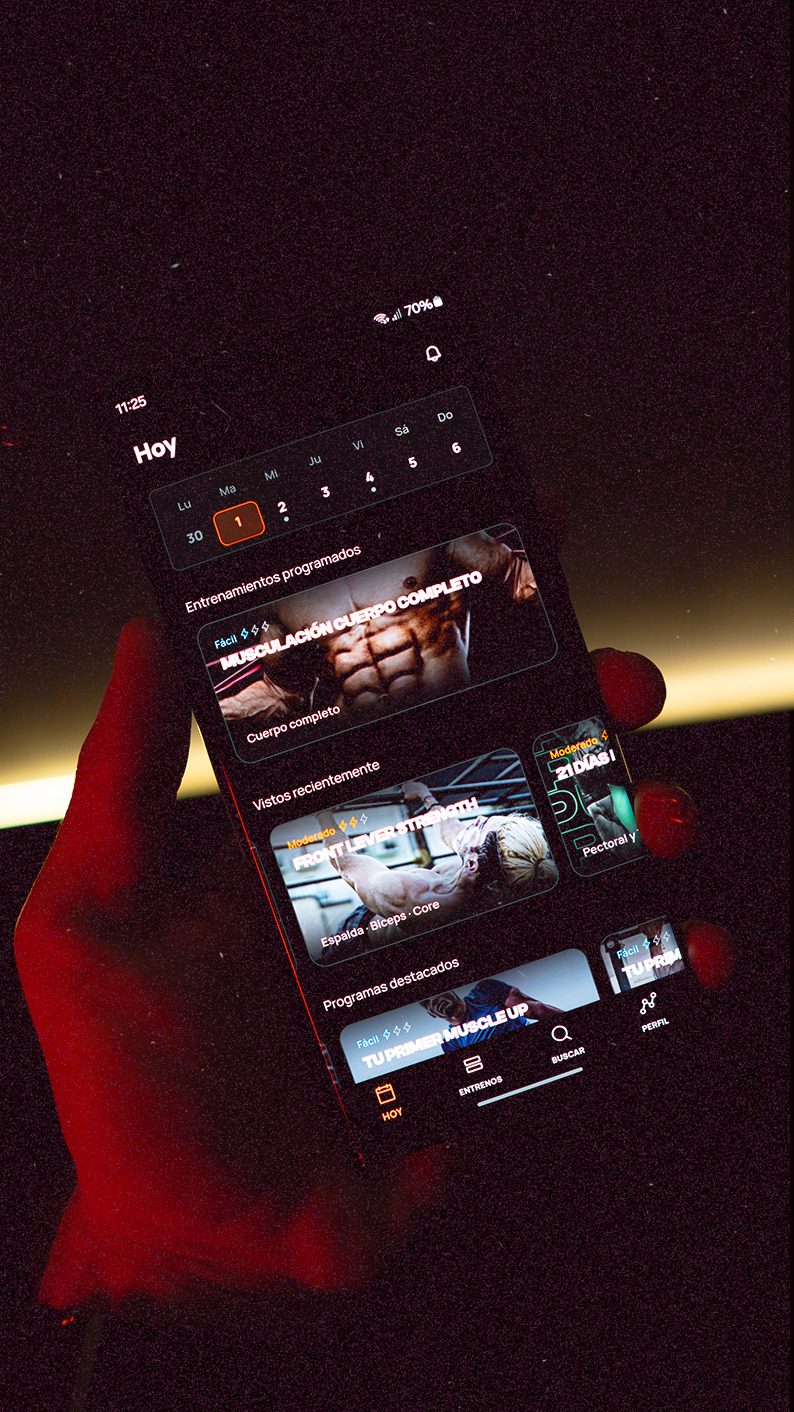

If you need training programs to help you practice these exercises (and perform them with strict form), check out the ones available on Calisteniapp—you’re sure to like them!

In conclusion, as we can see, athletes have a certain responsibility to be honest with their strict technique and full range of motion, especially outside of competition. However, it’s also true that the competitive scene often sets the standard that other athletes follow. That’s why it would be great if judges and competitions placed more emphasis on enforcing the rulebook and staying true to the values of calisthenics.

There’s one specific case where I think this is much more strictly enforced: Streetlifting, or weighted calisthenics. In this discipline, judges are much more careful to ensure athletes strictly follow the rulebook. Lockouts, range of motion, and other technical aspects are far more respected, and judges are not as lenient.

Of course, since Streetlifting competitions are based on a single repetition, it’s much easier to enforce strict standards. Meanwhile, in endurance competitions, there’s a frantic pace where athletes are performing dozens or even hundreds of reps as fast as possible.

We’ll see if, over time, we improve in these areas and continue building and refining such a beautiful sport as calisthenics.

By Yerai Alonso

Personalized quiz

Answer 7 quick questions and we will recommend the program that fits you best.

Yerai Alonso

Cofundador de Calisteniapp, referente en calistenia y el street workout en Español. Con más de una década de experiencia, es creador de uno de los canales de YouTube más influyentes del sector. Autor del libro La calle es tu gimnasio, campeón de Canarias y jurado en competiciones nacionales e internacionales.

Join our newsletter

Learn everything you need to know about calisthenics

Learn how to achieve your first pull-up from scratch with simple progressions, key exercises, common mistakes, and tips to progress faster.

Master the front lever with this step-by-step guide. Learn everything from correct technique and muscles worked to the most effective progressions and key exercises in calisthenics.

Discover the best calisthenics biceps exercises. Learn how to build arm strength without weights using bodyweight movements, effective progressions, and expert technical tips.